|

A delightful part of my part-time job as Manager of Ceramics at the Northampton Community College (NCC) East 40 is firing the wood kiln there! I had fired that kiln a number of times before, but for this Fall’s firing, I took on more of the work than in previous firings. I made the cone packs, for example, and made more of them than we had ever used in a single firing. Cones are scientifically formulated to bend over at very specific levels of “heatwork.” Heatwork is a matter of both time and temperature. The example I always give is lasagna. The oven may be 400 degrees, but if you only leave the lasagna in for five minutes, it’s not going to be cooked through! On the other hand, even if the oven is only 350 degrees, if you leave it in for 40 minutes it’s probably going to be fully cooked. Cones measure to what degree the ceramic is “cooked,” much like how a meat thermometer measures the temperature of the meat itself, not just the air in the oven. It was the first time I actually got to load a wood kiln, which takes a surprising amount of skill, not to mention hoisting really heavy silicon carbide shelves into place. All the hours I had spent watching others load wood kilns was invaluable. The idea is to understand how the flame moves through the kiln, and much like playing pool where one ball bounces off another, you want to bounce the flame onto all the pots, ideally send the flame everywhere, reaching every pot without restricting the path through the kiln. No pot can touch, or even get too close to touching, yet you have to do a kind of Jenga where you get as much work into the kiln as possible. The way ash moves through and lands on the work is another consideration. Suffice it to say it was an honor, and I was holding my breath that certain decisions I had made would work out! For example, Kelly Allen noted that no one had ever put the center shelves as far to the front as I had. Yikes! I was hoping for better flow through the kiln, more ash, but what if it just meant that the work closer to the front door didn’t get hot enough? Gulp. The door for the kiln gets built for every firing! First, the bricks. I actually really enjoyed custom fitting the last brick at the top of the arch, you can see it’s a lighter color than the bricks next to it. In previous firings we had done two bricks that stick out beyond the others, so you could remove them and see the cone packs strategically placed in the kiln for that purpose. For this firing, in addition to the two “peep” bricks, a third one with a hole in the middle was set up as a “blow hole.” Long story short, when flame is no longer coming out of the blowhole, you know it’s time to stoke. After the bricks were in place, Gabby Gentile (professor at NCC) and I “mudded” the door, which is pretty much like it sounds, although we used wet reclaim clay, not the kind of mud you have in a garden. Nothing like hands wet with “mud” in the winter. Then, for extra help so not so much heat escapes from the “door,” a special high-temperature cloth that looks like cotton but is not flammable, supported with a wire mesh was placed over the door. The pots were all loaded, the kiln was ready; but we had to leave it like that for weeks waiting for the burn ban to be lifted.

0 Comments

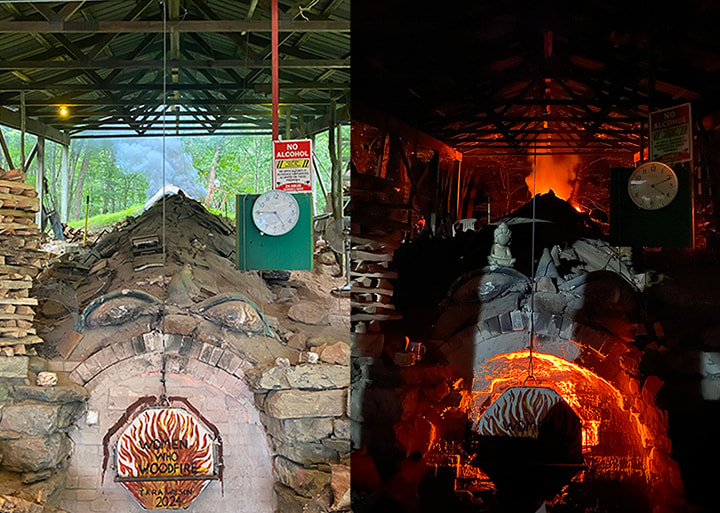

Even without the added eyeballs and horns, the anagama kiln at Peter’s Valley would look like a dragon. It only gets fired once per year, it takes a lot of wood and a lot of people power to fire this 57 foot long kiln-and that’s exactly what I was up to for this past week. As I write this, the kiln is cooling down, I will post again after the unload which is coming up this Sunday. I worked nights, and hung out during the day as much as I could when I wasn’t sleeping. The workshop was led by the Tara Wilson, an amazing artist with a trove of woodfire experience. Charlie Lid was on overnights (among a lot of other things), a veritable brain trust who has fired this kiln 22 times and made repairs to it. The staff at Peter’s Valley is awesome, all in all it was a great group of people. From loading to finishing was all interesting, but my favorite part was the overnight crew firing the kiln. Each night got hotter, and the last night was just nothing short of magical. We were giving the kiln exactly what it wanted (with Charlie’s interpretations) and it responded. In a few hours, we side-stoked over 900 pieces of wood, and that not counting what was put in the main firebox at the mouth of the kiln. There was music on, and all of us at some point were literally dancing; there was so much joy, we were dancing with the kiln. It’s an experience I will never forget. It’s hard to come up with words that describe the sheer power and elemental force of the flames within the kiln, that on that last night refused to be contained by the lids on the stoke holes, or the damper at the end of the kiln. Note that in the above photo and video, there is nothing “open” on the kiln; there are lids on the stoke holes and a big solid damper covering most of the end of the kiln-but the fire was so powerful that after we would stoke, it would erupt like a volcano from the slightest of gaps.

I harvested more than on June 19, but I used about the same amount of water when I processed it. This led to a super-concentrated batch, which of course led to new discoveries. More on that later in the post. I decided after adding the wood ash (to bring the PH up to 10) but before pouring it back and forth between the buckets (to oxygenate) to dye a bamboo rayon scarf. As is usual with both woad and indigo, when the vat is reduced (low oxygen) it’s a deep green, and so is the fabric when you first pull it out. But then when exposed to air (oxygen) it turns a true blue. In the case of fresh woad leaves like I was using, there is a significant amount of fugitive yellow in the leaves; and when I dyed the scarf, I had done nothing to get rid of that yellow. In any case-the scarf ended up a really lovely blue; so lovely it’s tempting to just keep it as is. But of course I’m curious about what if…I’ll get to that later. But now onto getting rid of the fugitive yellow. After dyeing the scarf, I did the pouring back and forth to oxygenate the infusion of woad leaves (I had already taken the leaves out, it’s like making tea.) Woad and indigo are actually pigments, that is, a solid; dye penetrates fiber, indigo and woad coat the fiber. When I used a higher water-to-woad ratio to make the “tea,” (see my last post) the heavier, solid pigment sank to the bottom, and the yellow liquid could be scooped or siphoned off the top. But this batch was SO PIGMENT HEAVY that the pigment didn’t settle at all-even after sitting overnight! I just went ahead and tried to strain it; normally, again, the yellow goes through the cloth and the blue pigment gets trapped on top of the filter cloth. But the “waste” water after I strained the liquid (first photo at the top of this post) was not yellow-it was really dark. Obviously there was a lot of pigment left, so I strained the “waste” water a second time. Sure enough, this second straining captured plenty more pigment on top of the cloth. Doing a more concentrated batch seems to be a great way to avoid lifting larger, heavier buckets! However, it means that the pigment won’t settle, and has to be strained at least twice. I’m kicking myself for not also dyeing a fabric swatch in addition to the scarf. That way I could cut the swatch in pieces, and try different stuff with the pieces to make comparisons. I wonder if next time I process woad, I gave the scarf an additional dip, if that would make the color deeper? I have this strange suspicion it wouldn’t do much! My reasoning is that there was SO MUCH pigment in that water, it was so concentrated, that the reason it didn’t go darker is chemical, not WOF (weight of fiber) to woad pigment ratio. So the second thing I want to do, is take some of the purified pigment, and reduce it again to make a dye vat, and then re-dye the scarf. My prediction is that without all the fugitive yellow still mixed in, the color of the fabric will go way deeper. Now I have to do another batch of woad, and put my theories to the test.

One last observation, woad is definitely a cut-and-come-again plant. The woad out at the NCC East 40 is happy that I’ve been persistently pulling the weeds to give it more room. Today-one day after I harvested the woad I’m showing in this post-you can’t even tell that I just harvested yesterday!  From left to right, the woad after ph was brought up to 10 and the liquid aerated. It looks green at left because the woad pigment, which is a solid, has not settled to the bottom. The other photos moving to the right are as more of the pigment settled; at right, I'm removing the clear yellow liquid with a turkey baster. Last year I had a bunch of empty flower pots and thought what the heck, let me see what happens if I grow woad in a small flower pot in my backyard-which does not get great sun. I should have harvested it last year, since first year woad is what you’re supposed to harvest. It blooms and goes to seed in the second year. But my back yard woad never flowered this spring, and I was curious if it was even worth harvesting such a small amount of leaves-only 50 grams worth, even though I harvested every leaf from the 4 pots. (See this post for how I process the woad.) The reason I decided to make this post, is that I put it in glass jars and photographed one of them as the woad pigment settled to the bottom of the jar. It’s just a good visual for that part of the process. In the last photo on the right above, I’m removing the yellow liquid with a turkey baster. The yellow is not a dye, it’s very fugitive and needs to get separated from the nice blue pigment. Results? Quite good! Not much quantity, because I had so few leaves, but especially for second year woad which isn’t supposed to work, it was a very rich, intense color. It was so close in quality to my last batch, that I just added what I got from this batch to that one. (My last batch was pictured in this post.woad-over-weeds-at-least-a-momentary-victory.html)

It’s a constant battle to pull out the weeds in my woad bed, to give the woad some room to grow. Woad-which has the most active ingredient (indigotin) we need for both dye and pigment-is harvested from first-year plants which grow very close to the ground. The local weeds jump up quickly, leaving the woad literally in their shadow. This past week I pulled wheelbarrows full of weeds out of the woad bed, and the woad responded almost in front of my eyes, I swear the woad was visibly more abundant by the end of the week. Tired as I was yesterday, I wanted to capitalize on this temporary moment of victory-so I harvested some woad. The weird thing was just how easy it seemed. I would compare it to making dinner; it took effort, yes, but it wasn’t like it sucked up the whole day, just one smallish part of a normal day. (If you want to see the whole process, reference this blog post.not-what-youre-supposed-to-harvest-in-october.html) I used less than 500 grams (about a pound) of fresh woad leaves. The first step is like making tea; you don’t boil the leaves, you pour the water onto the leaves and let them steep. You’re supposed to weight the leaves down, so they are surrounded by water during the steeping; I’ve used bricks inside of tupperware and all kinds of crazy things to try to do this, but last night’s innovation was I just stuck my tea kettle (with water in it for weight) on top and it was so easy! The kettle of course has a handle, so it was easy to lift the kettle and stir occasionally. O.K., not exactly earth-shattering but when you do something enough times, all these little discoveries and refinements help to streamline the process, and make it easier. I got a good yield of super-dark, rich pigment. (See right above) Once I dry the pigment into powder, I like to put each batch into its own little jar. I can compare the color of batch to batch that way, and this batch was definitely top-notch. For comparison, once I did a huge batch, and just didn’t have the patience to wash/strain out all the (non permanent) yellow from the liquid, long story short. I just dried the slurry as-was, and it was a lighter, kind of greenish blue, not the “true blue” that I just got in this smaller batch. So, I put the powder in a nice transparent glass jar and have kept it in the sunniest window in my house. The blue woad pigment is permanent, the yellow not permanent. In the 2 years that the pigment from that batch has been in my window, it has become increasingly blue! I would be wary of using that batch for a painting that I want to last indefinitely, but it was a fun experiment. Even after two years though, it’s not as good as the much more pure batch I made yesterday. Moral of the story I think, is make more small, easy to do batches.

In my first post on my new series of Medieval inspired ceramics, medieval-inspired.html I wrote that “So far only a few of these pieces been glaze-fired.” I think one of the strengths of this whole series is the interaction between a traditional thrown form with decorative/geometric/abstracted elements and incomplete figurative elements. An essentially one-color glaze keeps the ambiguity and imaginative leaps that the viewer can enjoy. I have come up with two strategies for making the glazes have some depth, variety and interest without getting contrived looking; local (and sometimes wonky) materials and wood kiln firing. As you can see from the vase above, glaze is not always going to hugely change the look of the piece. Even with the different background, lighting and point of view, this vase didn’t change its essential character when glazed. I formulated the glaze that I used featuring rock that I picked up off the side of route 611 in Easton. You might think that I could have used just any white glaze; but look closely at the comparison photos below. On the left, the vase was glazed with the glaze that I inherited in the ESU studio, with all commercial ingredients. On the right, another vase glazed with my rock glaze; I know it’s not a huge difference, but I prefer the rock glaze. So on the one hand, the glazing doesn’t necessarily radically alter the look of the piece from its pre-glazed state. But on the other hand, the glaze-and how it’s fired-really do matter, and give not only practical advantages like hardness and waterproofing, but improve aesthetics as well. The vases above were fired in an electric kiln; the first post I made about this series showed work that was fired in a one-day wood kiln firing. Wood kiln firings can have many serendipitous effects, between wood ash landing and melting onto the work (that was probably how glaze originated) fire hitting the work and the reduction atmosphere which causes both the clay and glaze to achieve different effects. The longer the firing, the more wood ash you are going to get, which is one of the reasons I’ve held off firing a number of my pieces; I will be taking the Anagama Wood kiln firing workshop at Peter’s Vally next month, where I can bring 30 pieces! Whether I’m using rock glazes or wood kiln firing (or both) my goal is the same; I want natural effects, not contrived painting/coloring.

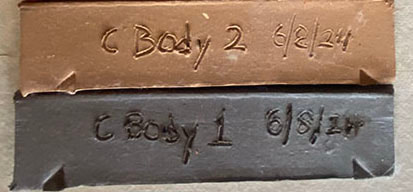

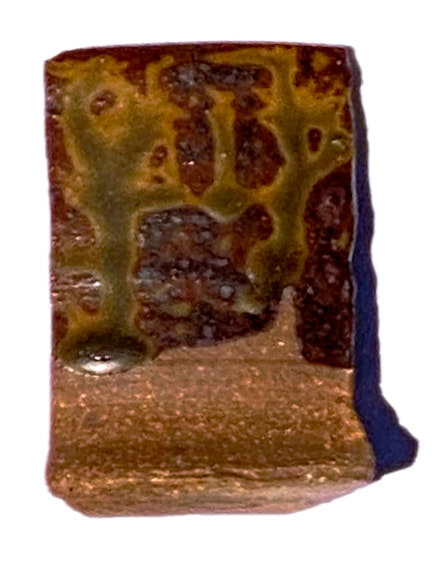

Vase made from the new clay body featuring East 40 clay. You can see the clay with no glaze at the bottom, and where I did strokes of wax resist as seen on the view to the left. A glaze featuring the East 40 clay was used at the top of the pot, you can see it's darker than the glaze below the neck of the pot.. As promised, some results from the test kiln firing. After making the part 1 post, I realized that it was just too technical for a blog post. I reached a kind of crossroads where I realized I needed to create a section of the website for technical information. If you want something more in depth than this post, go to my new Ceramics-Technical page, and the pages that branch off of it. The little test kiln did reach cone 10 (approx. 2,381 F) but not without a battle of many hours in the sweltering heat. Luckily, it was worth it. The firing gave us really critical information; how will the new clay body behave at high-fire temperature in reduction (oxygen starved) kiln atmosphere, which is how we fire the wood kiln? And, how will the 25 glaze recipe variations with the East 40 clay look and behave on the new clay body? Overall, the results were a smashing success. Both clay body, glazes, and the way the glazes look on the clay body passed with flying colors. Again, I'm not going to go into all the technical results here, but I do want to show you some of the highlights of what came out of the little kiln. In the test bars above, you can see the color of the clay with no glaze for yourself. In addition to the tile in the test kiln firing, the dark one at the bottom of the photo, Gabbry Gentile was kind enough to fire the one on top in the electric kiln up at the ceramics studio in Penn Hall on the main campus. I formulated this clay body for high temperature firings like we do in the wood kiln at the East 40; the real shocker, was that this clay body works at the medium range temperature used in the studio on campus! I won't go into the technical details here, but suffice it to say I was honestly shocked at how well this clay performed in an electric kiln at mid-range temperature! Ash glazes are supposed to show dramatic drips; the trick is, you don't want them to run off the pot. This test tile was photographed on its back because of sun glare, but it was standing up on vertical when fired in the kiln. The pleasant surprise was that all the variations of the ash glaze stayed up on the tile, none of them ran off the tile at the bottom which is a big problem with a lot of ash glazes. Many ash glazes can only be used at the top of the pot, they are so runny. This was the runniest variation, and even it didn't run off the tile. Long story short, we already have usable glazes based on the East 40 clay and wood ash, and they work great on the new clay body! Above is the simplest glaze recipe I tested-and my favorite result! The drips are less dramatic without the eggshell. It's such stable glaze that I can see using it on an entire pot, not just at the top for a drippy effect. The color comes primarily from whatever is in the East 40 clay, educated guess, a lot of iron.

Getting back to the vase at the top of this post, the dark part at the top is the same as the tile above, except there is an addition of copper oxide. The pot was first dipped in a glaze we had on hand from previous wood kiln firings, we wanted to see how it worked on the new clay body. The red you see, especially on the view to the right is actually from the copper-rich glaze I was testing at the top! All in all, we got lots of very helpful information from the test kiln firing. In all honesty, I didn't expect this much success in a first time at full-temperature firing!  Interior of the wood kiln at the Stahl's Pottery. You can see where the flame, heat and smoke came up from the 4 fire boxes in the floor; the pottery was put into other plain pots called "saggers" which were stacked floor to ceiling before the kiln was fired. 16 vents in the roof provided a draft to the chimney. I had two main reasons for going to the bi-annual Stahl Potter festival on June 15. One, I found out James Chaney, who I studied with 1978-80, was going to be there and I just had to tell him in person how great his instruction had been, and how I was building on it all these years later. The other of course was to see the historic pottery, and in particular the wood burning kiln.

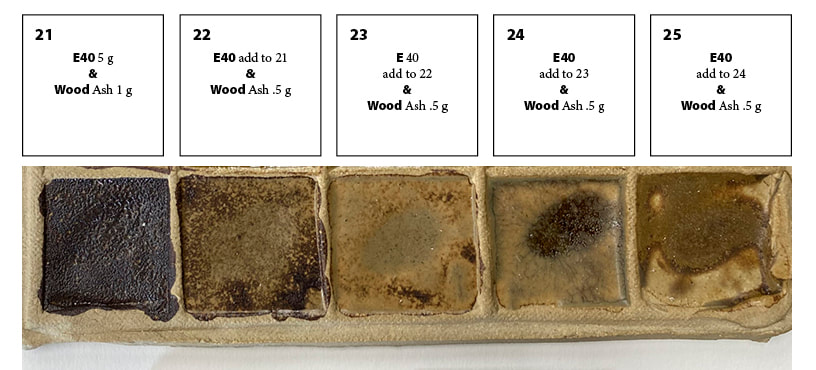

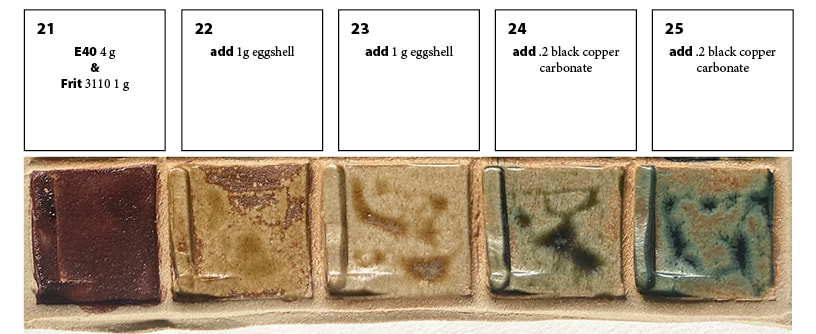

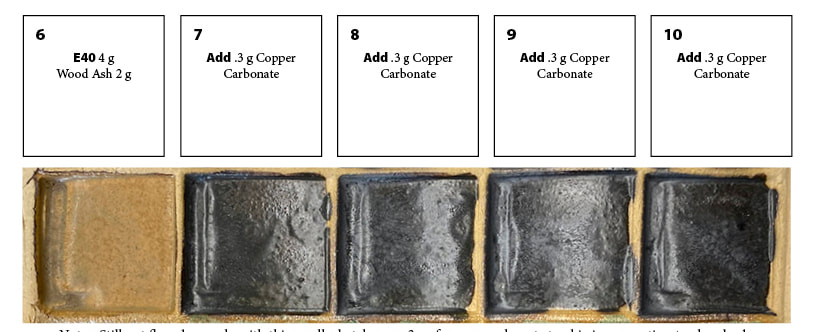

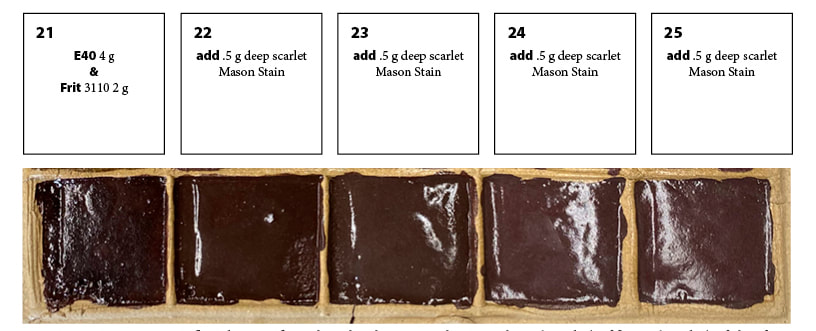

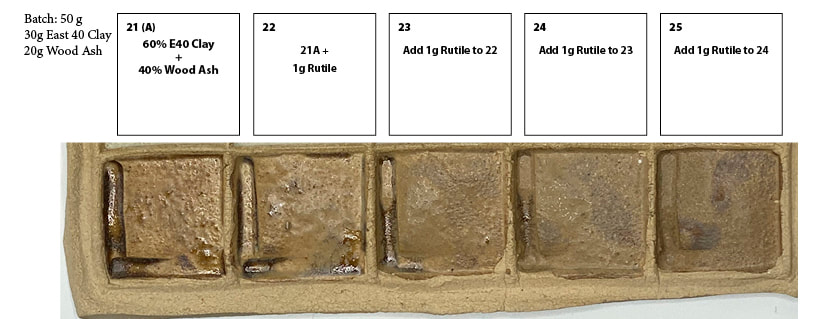

Not long after I met the man who has now been my husband for 25 years, he asked me what kind of architecture I liked best. It’s not a question anyone had asked me before, but my pause was under a minute; Victorian Gothic. What might practitioners of Victorian Gothic such as A. W. Pugin or John Pollard Seddon, for example, possibly have to do with a Pennsylvania Dutch Pottery-or Colonial Revival for that matter? Yes, I know this seems very fractured, but it was the trip to Stahl’s Pottery, and reading the book “Stahl’s Pottery of Powder Valley” that connected the dots. My mother despised all things Victorian and idolized all things colonial, so that adds a family historical twist to this aesthetic conflagration. Let me begin to unpack this aesthetic cacophony. The book has a chapter “Arts and Crafts and the Colonial Revival” and the “Arts and Crafts Movement” was invoked on multiple occasions as I toured the pottery and museum. When I think “Arts and Crafts” I think of 19th century and especially British artists; William Morris and Edward Burne-Jones for example, and if American, maybe Gustav Stickley, not of Colonial American revival. But there are commonalities, and my visit to the Stahl pottery got me thinking about them-and my own heritage. It’s easy to think of any revival, be it Victorian Gothic, Colonial or Arts and Crafts Movement, as an imitation; as something less-than the original. But William Morris, whose designs are still popular, did not simply copy older prototypes-he made new designs for a new age, an age that keenly felt the loss of the individual craftsman in mass-manufacture. (It’s a bit mind-breaking that mass manufacture is overwhelmingly how those of us in the twenty first century have ready access to his designs.) And that was the big epiphany-that these “Historiated” styles, when done right, are new inventions originating out of the needs and circumstances of their own times, not less-than imitations of something that is done and over. The Stahl brothers learned pottery from their Victorian father. In the early twentieth Century they shut down the pottery they inherited/tried to carry on from their father, because they couldn’t compete with mass-manufacture. But they opened their own pottery three decades later because the values of the Arts and Crafts movement begun in the nineteenth century had taken root here, in the twentieth century, and the literal value of the kind of work they had done for their father had multiplied. In the midst of the Great Depression no less, the Stahl bothers opened an old style pottery with wood kiln, what is now the Stahl’s Pottery Historical site https://www.stahlspottery.org. I didn’t see my mom’s fascination with the colonial as more than her personal taste; I didn’t see it as part of a larger historical phenomenon. My mother seldom could use the word “Victorian” without the accompanying adjective “monstrosity.” (I suppose my way of rebelling against my mom was a Victorian aesthetic.) I was missing the through lines, of Arts and Crafts, Colonial Revival and my own aesthetics. The Stahl brothers weren’t imitating the work of previous potters; they were doing their own work. The interesting thing with arts and crafts is that when you do things with your own hands, it’s actually hard not to put yourself into what you’re doing, even if you’re using traditional materials and techniques. And those who pick up those pots, or look at those paintings or wear that hand knitted sweater etc. see that human element, which only becomes more precious the more impersonal products become in our society. This summer I am working to formulate glazes and a clay body from the local clay dug from the Northampton Community College (NCC) East 40. https://www.ncceast40.org I’m weird; for me, waiting for the next glaze test to come out of the kiln is like a kid trying to wait to unwrap a present. But while I’m waiting for the tests that will come out of the kiln on Thursday, I thought I’d make a post about the preliminary testing I’ve already done. Spoiler alert-I’m going to show you the best first, see above. To set this up, you have to realize that the clay at the East 40 is very rich with ingredients (probably iron, maybe manganese) that go very dark when fired to the high temperatures (roughly 2,380 degrees) we use for our glaze firings. I discovered a “magic powder” from my kitchen, that makes the East 40 clay fire light, and opens up striking color possibilities! I get eggs from a local farm, and if you’re familiar with truly free-range eggshells, you realize they are at least twice maybe three times as thick as factory farm eggshells. That's why eggshells build up fast at my house! Eggshells are on average 95% calcium carbonate, and calcium carbonate is one of the most common and useful ceramic ingredients. In glazes, calcium carbonate is usually sourced from whiting or talc. Eggshells, when fired, shrink in volume tremendously, which can cause problems in glazes. I did a preliminary bisque firing of my ground up eggshells, so that the shrinkage would happen BEFORE I put them in a glaze. You can see on the left in the line blend above, how dark the East 40 clay fires even though tis test was fired at a lower temperature than we use in the gas and wood kiln firings at the East 40. But wait! Add a little eggshell, (second from left square) and the color changes. Add a little more (center) and wow, a totally different glaze color, without adding any colorant!! But wait, there’s more. Add a little black copper oxide (colorant) and you get one green, a tiny bit more and you get a different green! I designed an entire 25 section biaxial tile-5 rows of squares by 5 rows of squares-investigating the interaction between 4 ingredients, as inspired by this line blend. All of the variations use the East 40 clay, and wood ash which is used as a flux (an ingredient to melt the clay into a shiny glaze). The balance of East 40 clay to wood ash is varied, explored both with and without the other two ingredients, the eggshells and the black copper oxide. Look for a post on when this tile comes out of the kiln!  Like the tile above, this was the last row of a 25 section tile. Note that on the left, there is not enough wood ash to melt the clay enough to make a smooth and shiny glaze. Moving to the right, I'm adding a little more wood ash in each square. by tile 25 it loses the rocky texture of the first tile, getting closer to a usable glaze. Adding Wood Ash to East 40 Clay This test uses only two ingredients. Going left to right, I added increments of more wood ash to the East 40 clay. A few notes about this; for the ceramic artists out there, this was cone 6 oxidation. It's obvious that the 5 parts clay to one part ash is not nearly enough ash. (The ash is used as a flux, that is, to help melt the clay into a glaze.) I made impressions into each square with a finger, making a kind of "lake" within each square, and also applied the glaze unevenly to see how various thicknesses of the glaze would work. I'm working with such tiny amounts here that of course more testing is needed to nail down percentages, but it's pretty clear that the wood ash I was using, which was from the wood kiln at the East 40, needs to be over half the mix to melt the clay. I'm currently working on glazes for cone 10, so at that hotter temperature obviously everything will melt more than at this cone 6 (lower temperature) test. Adding a colorant I wish I had done the line blend of just the clay and wood ash first! Here there isn't enough wood ash in the mix to start, and as you add a colorant like copper carbonate, that tends to retard melting and make matters worse. Note that even .3 grams is way too much colorant for a first step! Instead of green, which we would expect from copper carbonate, we're almost at black. That's why I start with simple line blends-I'm not using much in materials to get this kind of information that points me in the directions I should go. Above, I used 4 g of East 40 clay to 2 parts of a commercially produced flux, the same percentage of clay to wood ash from the last test. The commercial flux has a stronger action but even so, it's under-melted. I'm using a commercial mason stain for the colorant. The main problem is that the clay when properly melted into a glaze is so inherently dark, it's hard to notice much color difference from the base glaze at left with no colorant. In the basic mix at left before I started adding rutile, it's melting ok but not great. Rutile can add color, texture and odd what I'll just call variations to the look of a glaze. Like the cobalt carbonate, it also makes the glaze more matte, or under-melted, under vitrified in ceramic terminology. Matte glazes are a thing, we don't always want super glossy glazes, but they can be more prone to leaching and other defects/weaknesses. I do want to do more tests with rutile going forward, just that every time I add an increment of rutile I know I need to add an increment of flux (melter) at the same time.

The way-back story I first used this clay when I was working on my master’s thesis, using a simple mix of half East 40 clay and half of a commercially available clay to make loom weights. (See crossing in my portfolio section) In my summer of 2022 Residency at the East 40, I used the clay, raw and roasted in a bonfire, as pigments for paints that I made and used in the “Imaginary Landscape” series of paintings that were featured in my Fall 2022 solo exhibition. During the residency, Walter Heath saw me grinding up rocks for pigments, and immediately had visions of using them to develop glazes. That summer I wasn’t ready to go there-but in 2023 I began preliminary testing, not just for the East 40 clay, but from local rocks I had picked up and processed. In this post I’m only showing the initial line blends I did with the East 40 clay, omitting all the rock glaze tests and tests on clay I dug out of my front yard-it’s a long enough post as is! There is something about the weirdness, and richness of Medieval Art that has been an inspiration to me ever since I can remember. But just in this past year, I came across a Medieval wine pitcher (see photo above) that pitched me into a new series of work in ceramics.

I love that this guy’s hands are circles with lines through them, and his arms a simple single string of clay. I love that we still see them as hands and arms; I could give many more examples on this and other pieces but the point is, it’s this leap of imagination that intrigues me. Bestiaries are another related concept in medieval art that inspires me, how species could be mixed and matched, and become a new creature such as a griffin. And finally, I have always loved the flat out decoration of Medieval and Gothic things, from buildings to furniture to textiles etc. What fascinates me about the Medieval decoration is how a very few simple geometic forms can become incredibly rich and varied with repetition. These three medieval inspirations-weird abstraction, mixing of species and repetitive ornament-became the basis for a whole series of work in ceramics. |

Cindy VojnovicArtist & Educator Archives

September 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed