|

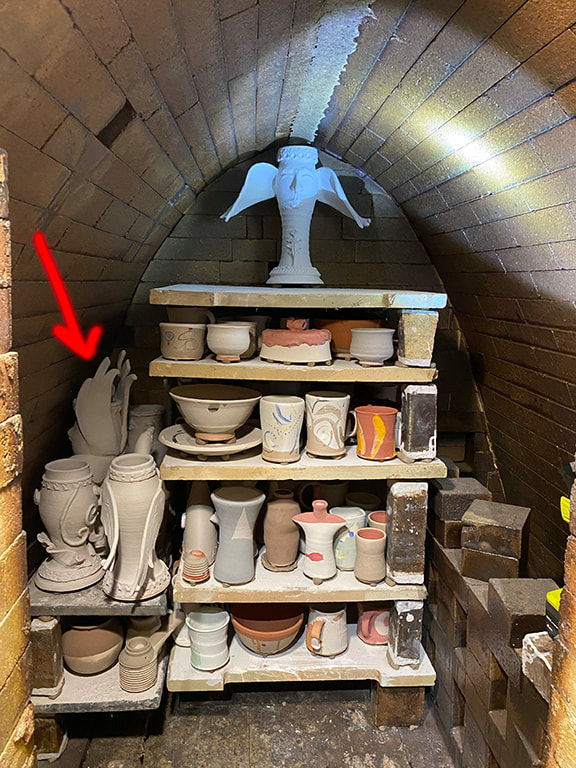

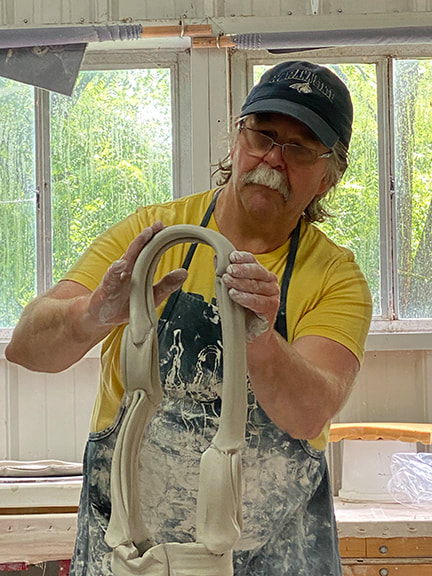

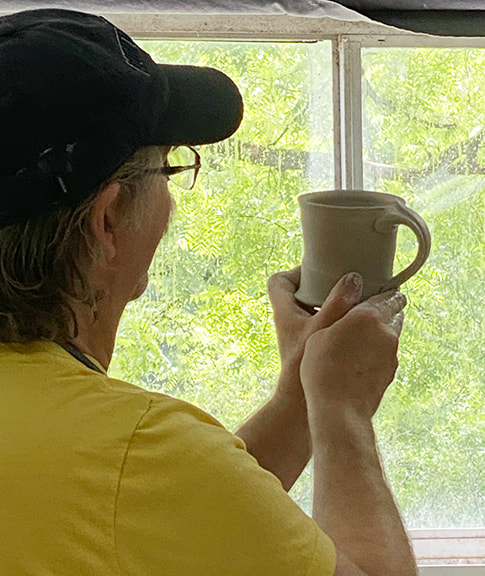

When Peter’s Valley announced this year’s workshop schedule, I was at first perturbed that they had shifted the firing of their anagama (see dancing with the dragon) from August, before fall semester begins, to mid-October. Then I noticed they had scheduled Josh DeWeese to do a workshop firing the noborigama. Josh DeWeese was a long-time director of the famous Archie Bray Foundation, and is a stellar artist I wanted to work with, so I took the plunge and signed up. A noborigama is a multi-chambered wood-fired kiln, and the workshop was shorter than theanagama one so I went in to the workshop expecting a kind of “anagama light” workshop that was essentially loading the kiln and firing it for the whole time. I certainly didn’t expect the actual firing of the kiln to be only 24 hours (after pre-heat) or all the demonstrations. I was expecting that, like the anagama, the outside of the work would be dominated by wood ash deposits turned to glass (glaze) by the heat, and that I would only be applying glaze on the inside of the pots, with little or nothing on the outside. The workshop began with Josh showing us his more elaborate process of glazing, suited to a shorter wood-fire and soda kiln. In the noborigama at Peter’s valley, the first chamber is wood only, and the second chamber is a soda-fire chamber. The soda jacks up the color response and flow of glazes. Applying glaze for that atmosphere (soda) was totally new for me, and to be honest, I didn’t really take advantage of much of the flood of information Josh gave us, especially not on my Medieval inspired vases. There were some in the workshop who did a very good imitation of Josh’s style, and got great pots as a result. But as much as I love Josh’s work-I was thrilled to buy a fabulous pitcher that he used in his glaze demo-but I just couldn’t instantly figure out how what he demonstrated could be used on my Medieval inspired work. Luckily I brought a bunch of mugs that were plain enough in form that I didn’t mind getting more elaborate with the glazing. I have to admit I did a pretty fast down-and-dirty glaze job on my pots, in part because as explained above, I knew I didn’t have the time to fully process how this glazing approach could work for the forms I brought to fire. The other reason was, I wanted to be right there for all the kiln-loading. Loading a wood kiln is a crucial part of the process, and one I’m keen to learn about since I actually get to do that at the NCC East 40 wood kiln. It was so exciting to see my work go into the kiln; it seems that catenary arch kilns just love my work. “I need something tall and skinny” is almost a cliché when loading a catenary arch kiln; my work loves snuggling up to the curved walls of the kiln. When they put in my Hypnos at the top of the arch, I had to snap a photo before all the rest of the work got packed in. I of course signed up for a double shift in the overnight, and figured if the firing didn’t end on my shift I would just stay until it finished anyway. I can’t lie, it felt a little weird doing a short firing with so many people. Last December I did a 24 hour firing at the NCC wood kiln, but there were way fewer people, and I did the last 17 hours of that firing non-stop. Before my shifts, I did a lot of hanging out at the kiln watching others do all the work, which was very strange for me. Firing the anagama for a full week, everthing happened slower. I felt like by the time I adjusted to the rhythm of this firing, it was over. A shorter firing means a shorter cool-down period. After the anagama, we left and came back the next week. But since this was only a 24 hour firing, we stayed while the kiln cooled. That was when Josh DeWeese switched into high gear, spending a whole day and the following morning in a marathon making demo. It made me tired just to watch him, 😂 ! His sense of humor was delightful, I don’t know how he managed to tell fun and illuminating stories while he made incredible work and simultaneously explained what he was doing and gave insightful tips. I frequently botch demos because I’m so busy trying to explain what I’m doing that I can’t do it. (Once I joked I can’t chew gum and walk at the same time, and one of my students, apparently never having heard that expression, took me seriously, and said “really?!”) I absorbed so much from Josh DeWeese!!! Not just technique, or art-but how to make a supportive positive space in which people can best learn. His teaching is nothing short of spectacular, he gets it right from every possible angle. Generosity is the term that springs to mind. He really gave of himself, and he’s got a lot to give. When we gathered to unload the kiln, he coached us; “the appropriate response when something comes out of the kiln is Ooh! Ah!!” He had us all reapeat the oohing and aching until we reached an appropriate level of positive enthusiasm. He said not to be dissapointed if something didn’t turn out as expected; to live with it before making judgments. That bit of advice I had heard before, but it is so true with woodfiring in particular. You often get something out of the kiln that is not at all what you were going for-and it can take a while to figure out if that’s a good or a bad thing. I felt like the pace of the workshop was perfect. I got enough rest that I could absorb all the new experiences and information like a sponge, but at the same time, there was never a dull moment. I’m still absorbing and working with what I learned, and will be for some time to come.

Finally, the thing that astounded me most about the Josh DeWeese workshop was that it did exactly what a vacation is supposed to do. I felt like I got out of the usual grind, experienced wonder, and gave me time to reflect on just how blessed I really am. It’s now a few weeks since the workshop and I’ve been working a lot, but that feeling is still with me.

0 Comments

I knew I wanted to use gold on my ceramics before I even knew why! Real gold will evaporate, “volatilize” is the technical term, if exposed to the high temperatures needed to fire the clays that I use. I confirmed this the hard way, three years ago I embedded some tiny bits of gold foil around the rim of a pot, and even in the preliminary “bisque” firing (not as hot as the final glaze firing) the pot emerged from the kiln without a trace of the gold. You’ve probably seen fine china that has gold trim or accents, for example around the edges. The way it’s done, is that you glaze and fire the whole thing first, without the gold, at the usual high temperature. Then, you apply the gold and fire at a much lower temperature to “fix” the gold permanently onto the ceramic. This is what’s called an “overglaze,” and what I finally got around to doing! With wood firing, you can’t control exactly how anything is going to come out, and honestly the serendipity of it is a huge part of the attraction. But sometimes a piece comes out of the wood firing and, well, needs some help. Well, I had some pieces that just needed a little oomph, a little spark, an accent.Two of them had a lovely, ivory colored satiny glaze surface; but they were to subtle, they needed an accent, some pop. On the other end of the spectrum, I had a piece with a kind of mottled surface, mostly quite dark. Finally, I had a piece that had quite nice “flashing”-effects of the fire on the clay, which highlighted the sculptural form really well-but the surface was quite dull and matte, no shine. Opening up a wood kiln is like unwrapping Christmas presents-you may have an idea what to expect, on the other hand, you can get some real surprises! What I find the most strange, is how difficult it can be to figure out if the surprises are good or bad. It can take months, even a year or more to really “digest” the serendipitous effects off flame, wood ash and the myriad variables of the firing. I had two sculptural, medieval inspired vases in the kiln, both had a salt-white glaze, and came out weirdly brown speckled. My first response was yuck, not what I had hoped for-and not what I had got from the same clay and glaze combination in Previous wood firings in the same kiln! In fact, there was another vase in this firing, same clay, same glaze, but it was a re-fire from the previous firing. In that previous firing, there were parts of the kiln that just didn’t get hot enough to properly melt the glaze. But this time, that pot came out with a kind of lovely glow-I’m so glad I re-fired it. But what of the two speckle monsters? Hmmm. Not so sure about those, have to sleep on that for a few months. Then there were the mug re-fires. These were all made from “C Body” East 40 clay, and had been through a 6 day anagama firing this past October. They too must have been in cold spots in that firing, the glazes were rough and underfed. This is a clay I formulated less than a year ago, so I’m keenly interested in putting it to the test in every way possible. I had pieces in the Peter’s Valley anagama firing, in locations of the kiln that got up to cone 11 (the clay was formulated for cone 10) and there was no trouble at all. No flaws of any kind in the clay. There were also no flaws after the October 6 day anagama firing-but this re-fire kind of “fried” them, since they were located in parts of the kiln that overshot the firing range of this clay body. Let me explain. We used cone packs that had two cones below our target, (cones 8 & 9) our target cone (10) and a “guard” cone of 11. In the photos, the order from left to right is 8,9,10,11. In the first photo, you can see a perfect 10.The number 10 cone (third from left) is making a perfect arc, the tip down to the level of the base. There is daylight under the arc, as there should be. By contrast, the lower temp cones 8 & 9 are no longer an arc, they are a puddle, and cone 11 is only beginning to bend. In the second cone pack, there is no daylight anywhere under these cones, even cone 11 is a melted puddle on top of the clay that held the cones in place. What this means is that in that section of the kiln, we blew past our goal of cone 10, and because 11 is a puddle we must have actually hit cone 12. I found out the hard way the upper limit of the C body clay; it was fine at cone 11, but cone 12 was just too much. One of them cracked early enough in the firing that the glaze hadn’t melted yet, since, the glaze healed over the crack completely. Another had little bloat bubbles. The work had been over-fired enough to become so brittle that several of them had chips that broke off the bottom where there was no glaze to support the clay. To be fair, they were really close to the firebox, which hit at least two cones above our target, as explained above. And in spite of the flaws in some of them, others have no visible flaws and they certainly didn’t melt into a puddle or even slump, which can happen when a low-fire clay is high-fired. I fired an odd little piece I had done as a demo for texturing slabs, and making a draped form with visible slab joins from them. On the inside I sprayed on the East 40 ash glaze (that I formulated) in a fairly thin layer, and the outside was a combination of two different shinos and a salt white glaze and a little bit of the East 40 ash. For a little throwaway pot-I was going to just recycle the clay after the demo, but decided to keep it to just to experiment with glazes-I’m surprised at how good it looks.

In short, the work I cared most about-the medieval inspired vases-came out just whatever, while the piece that took me 10 minutes to make came out great. Or at least that’s what I think today. Maybe I’ll wake up in 6 months and have a totally different opinion. Please comment and let me know what you think! In my first post on my new series of Medieval inspired ceramics, medieval-inspired.html I wrote that “So far only a few of these pieces been glaze-fired.” I think one of the strengths of this whole series is the interaction between a traditional thrown form with decorative/geometric/abstracted elements and incomplete figurative elements. An essentially one-color glaze keeps the ambiguity and imaginative leaps that the viewer can enjoy. I have come up with two strategies for making the glazes have some depth, variety and interest without getting contrived looking; local (and sometimes wonky) materials and wood kiln firing. As you can see from the vase above, glaze is not always going to hugely change the look of the piece. Even with the different background, lighting and point of view, this vase didn’t change its essential character when glazed. I formulated the glaze that I used featuring rock that I picked up off the side of route 611 in Easton. You might think that I could have used just any white glaze; but look closely at the comparison photos below. On the left, the vase was glazed with the glaze that I inherited in the ESU studio, with all commercial ingredients. On the right, another vase glazed with my rock glaze; I know it’s not a huge difference, but I prefer the rock glaze. So on the one hand, the glazing doesn’t necessarily radically alter the look of the piece from its pre-glazed state. But on the other hand, the glaze-and how it’s fired-really do matter, and give not only practical advantages like hardness and waterproofing, but improve aesthetics as well. The vases above were fired in an electric kiln; the first post I made about this series showed work that was fired in a one-day wood kiln firing. Wood kiln firings can have many serendipitous effects, between wood ash landing and melting onto the work (that was probably how glaze originated) fire hitting the work and the reduction atmosphere which causes both the clay and glaze to achieve different effects. The longer the firing, the more wood ash you are going to get, which is one of the reasons I’ve held off firing a number of my pieces; I will be taking the Anagama Wood kiln firing workshop at Peter’s Vally next month, where I can bring 30 pieces! Whether I’m using rock glazes or wood kiln firing (or both) my goal is the same; I want natural effects, not contrived painting/coloring.

There is something about the weirdness, and richness of Medieval Art that has been an inspiration to me ever since I can remember. But just in this past year, I came across a Medieval wine pitcher (see photo above) that pitched me into a new series of work in ceramics.

I love that this guy’s hands are circles with lines through them, and his arms a simple single string of clay. I love that we still see them as hands and arms; I could give many more examples on this and other pieces but the point is, it’s this leap of imagination that intrigues me. Bestiaries are another related concept in medieval art that inspires me, how species could be mixed and matched, and become a new creature such as a griffin. And finally, I have always loved the flat out decoration of Medieval and Gothic things, from buildings to furniture to textiles etc. What fascinates me about the Medieval decoration is how a very few simple geometic forms can become incredibly rich and varied with repetition. These three medieval inspirations-weird abstraction, mixing of species and repetitive ornament-became the basis for a whole series of work in ceramics. |

Cindy VojnovicArtist & Educator Archives

September 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed