John Britt with SOME of the tiles he brought with him, showing the logic of what we were doing in the workshop. He had 40+ base glazes, and a sheet with 11 colorants that would get added to each glaze. Each person in the workshop made a different base glaze, made 11 different versions and applied each of those to tiles made from 3 different kinds of clay. There are thousands and thousands of glaze recipes online and in print. But John Britt’s books have such a well organized variety, I just don’t bother looking elsewhere. His YouTube free glaze class is amazing, when I came back to ceramics after many years, it not only removed the rust from what I could remember but gave me a more thorough understanding than I had before. I really didn’t want to do another workshop so soon after the Josh DeWeese one at Peters Valley, but it was John Britt close to home, how could I pass it up? After making my own paint, I already had ground up rock when I started teaching ceramics, so it was a pretty natural segue for me to start formulating glazes. It’s true I also listened to lots of Phil Berneberg’s videos and read a bunch of good books, but John Britt is definitely my glaze hero. As much as I’ve learned on my own, I had never taken a class specifically in glazes. John was so systematic and organized in the way he structured the class that it helped me organize my own thinking about glaze development, and how I might present things to my more advanced students. The workshop was hosted by Kettle Creek Pottery, a really lovely pottery studio owned by Amy Manson. It was a great group of people. My moment if glory is when John asked me if he could show my notebook to the class! I got a photo of him holding up my notebook which I of course pasted into that notebook.

0 Comments

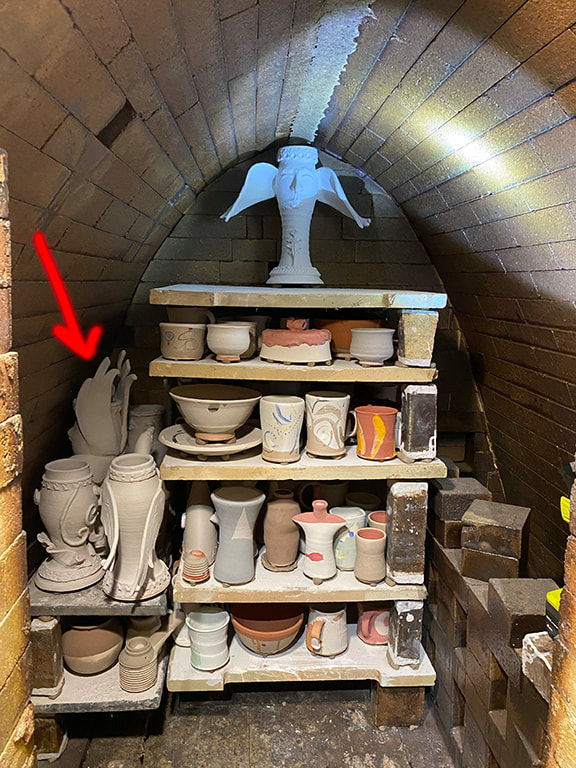

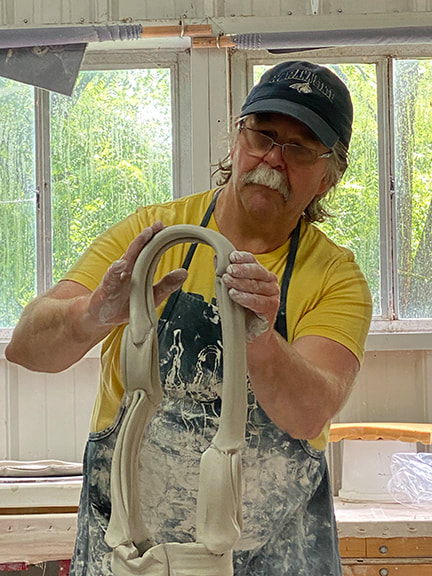

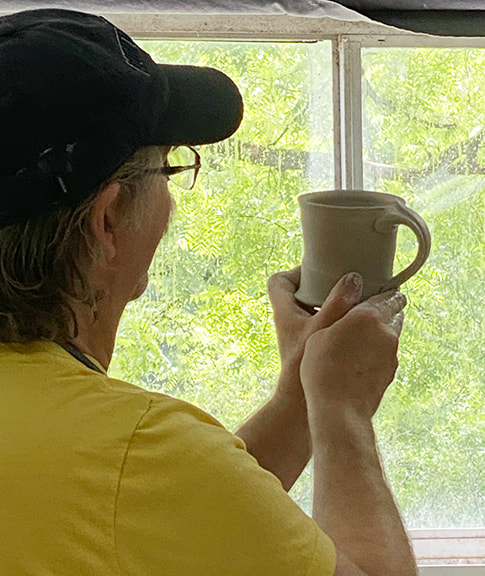

When Peter’s Valley announced this year’s workshop schedule, I was at first perturbed that they had shifted the firing of their anagama (see dancing with the dragon) from August, before fall semester begins, to mid-October. Then I noticed they had scheduled Josh DeWeese to do a workshop firing the noborigama. Josh DeWeese was a long-time director of the famous Archie Bray Foundation, and is a stellar artist I wanted to work with, so I took the plunge and signed up. A noborigama is a multi-chambered wood-fired kiln, and the workshop was shorter than theanagama one so I went in to the workshop expecting a kind of “anagama light” workshop that was essentially loading the kiln and firing it for the whole time. I certainly didn’t expect the actual firing of the kiln to be only 24 hours (after pre-heat) or all the demonstrations. I was expecting that, like the anagama, the outside of the work would be dominated by wood ash deposits turned to glass (glaze) by the heat, and that I would only be applying glaze on the inside of the pots, with little or nothing on the outside. The workshop began with Josh showing us his more elaborate process of glazing, suited to a shorter wood-fire and soda kiln. In the noborigama at Peter’s valley, the first chamber is wood only, and the second chamber is a soda-fire chamber. The soda jacks up the color response and flow of glazes. Applying glaze for that atmosphere (soda) was totally new for me, and to be honest, I didn’t really take advantage of much of the flood of information Josh gave us, especially not on my Medieval inspired vases. There were some in the workshop who did a very good imitation of Josh’s style, and got great pots as a result. But as much as I love Josh’s work-I was thrilled to buy a fabulous pitcher that he used in his glaze demo-but I just couldn’t instantly figure out how what he demonstrated could be used on my Medieval inspired work. Luckily I brought a bunch of mugs that were plain enough in form that I didn’t mind getting more elaborate with the glazing. I have to admit I did a pretty fast down-and-dirty glaze job on my pots, in part because as explained above, I knew I didn’t have the time to fully process how this glazing approach could work for the forms I brought to fire. The other reason was, I wanted to be right there for all the kiln-loading. Loading a wood kiln is a crucial part of the process, and one I’m keen to learn about since I actually get to do that at the NCC East 40 wood kiln. It was so exciting to see my work go into the kiln; it seems that catenary arch kilns just love my work. “I need something tall and skinny” is almost a cliché when loading a catenary arch kiln; my work loves snuggling up to the curved walls of the kiln. When they put in my Hypnos at the top of the arch, I had to snap a photo before all the rest of the work got packed in. I of course signed up for a double shift in the overnight, and figured if the firing didn’t end on my shift I would just stay until it finished anyway. I can’t lie, it felt a little weird doing a short firing with so many people. Last December I did a 24 hour firing at the NCC wood kiln, but there were way fewer people, and I did the last 17 hours of that firing non-stop. Before my shifts, I did a lot of hanging out at the kiln watching others do all the work, which was very strange for me. Firing the anagama for a full week, everthing happened slower. I felt like by the time I adjusted to the rhythm of this firing, it was over. A shorter firing means a shorter cool-down period. After the anagama, we left and came back the next week. But since this was only a 24 hour firing, we stayed while the kiln cooled. That was when Josh DeWeese switched into high gear, spending a whole day and the following morning in a marathon making demo. It made me tired just to watch him, 😂 ! His sense of humor was delightful, I don’t know how he managed to tell fun and illuminating stories while he made incredible work and simultaneously explained what he was doing and gave insightful tips. I frequently botch demos because I’m so busy trying to explain what I’m doing that I can’t do it. (Once I joked I can’t chew gum and walk at the same time, and one of my students, apparently never having heard that expression, took me seriously, and said “really?!”) I absorbed so much from Josh DeWeese!!! Not just technique, or art-but how to make a supportive positive space in which people can best learn. His teaching is nothing short of spectacular, he gets it right from every possible angle. Generosity is the term that springs to mind. He really gave of himself, and he’s got a lot to give. When we gathered to unload the kiln, he coached us; “the appropriate response when something comes out of the kiln is Ooh! Ah!!” He had us all reapeat the oohing and aching until we reached an appropriate level of positive enthusiasm. He said not to be dissapointed if something didn’t turn out as expected; to live with it before making judgments. That bit of advice I had heard before, but it is so true with woodfiring in particular. You often get something out of the kiln that is not at all what you were going for-and it can take a while to figure out if that’s a good or a bad thing. I felt like the pace of the workshop was perfect. I got enough rest that I could absorb all the new experiences and information like a sponge, but at the same time, there was never a dull moment. I’m still absorbing and working with what I learned, and will be for some time to come.

Finally, the thing that astounded me most about the Josh DeWeese workshop was that it did exactly what a vacation is supposed to do. I felt like I got out of the usual grind, experienced wonder, and gave me time to reflect on just how blessed I really am. It’s now a few weeks since the workshop and I’ve been working a lot, but that feeling is still with me. I get so tired out doing stuff it’s hard to find the time and energy to blog about the stuff I’m doing. As I sat down to finally make a new blog post, I wondered, should I blog about my show at Book & Puppet being extended, the progress of my weaving at that show, the dye classes I’ve done in the past month at the NCC East 40, my upcoming classes there, my latest ceramic creations, my imminent trip to Peter’s Valley for a workshop with Josh DeWeese to fire their Noborigama kiln or…? On Saturday evening I went with my husband to Columcille for their first ever celebration of Midsummer Gloaming. (I deliberately spelled it wrong in the title for this post in honor of Midsommer Murders.) I’ve never been really big on “New Year” being January 1, it just seems so arbitrary. Marking our planet’s position in the universe just seems a much better moment for reflection. In taking icon classes with master iconographer Vladislav Andrejev stressed the circular nature of idea or intentions, followed by practice followed by reflection which would inform the next round of intentions and so on. Midsummer Gloaming just seems like a great time to step back, and try to transform the laundry list of things I’ve been/am up to lately into some kind of inflection point. The show at Book & Puppet is a kind of 4 years retrospective, it brings the facets of my artistic practice into a one place. I’m dyeing (pun intended) to finish the weaving-and wondering how many people will “get it.” I can’t say more than that-I want people to interpret it for themselves, and see if anyone can see what I am intending. This show is really the inflection point; it connects my past number of years with the literal creation of new work right in the gallery.

Looking at one of the rocks at Columcille, I noticed lichen growth. And then I noticed ants, a caterpillar and other insects; the fact that life was literally springing forth from a rock was pretty mind-blowing. Take the time to look closely, to see an everyday miracle. You won’t look back on this moment in your life and fondly remember your to-do list. Take time for a moment of wonder. @ Book and Puppet March 15 – June 7 2025 Loom raising 5-8 Friday March 28 Reception 3-6 p.m. Saturday April 26 This coming week I am going to be hanging a solo exhibition” curated by Arta Brito that brings together my recent work from the past few years, the fiber, painting and ceramic. I was so happy that Arta could see the connection between growing plants to dye recycled fabric and make paints, for example, with making clay and ceramic glazes from local materials. I’m literally going to the earth for my materials, and participating in historical, even ancient forms of making. In a world that is becoming ever more virtual and artificial, I hope people can enjoy the “grounding” of this work when viewing it as much as I felt when making it. The fixed parts of the show will be up by March 15, available for viewing during all of Book & Puppet’s regular hours. There will be a “loom raising” event on Friday March 28, the public is invited to come and help me construct a warp-weighted loom in the gallery! I will demonstrate how I take old bed sheets, clothing etc. and turn them into cord or “t-shirt yarn” that can be used for weaving. I’m going to use the loom and naturally dyed, repurposed fiber to do a weaving on this loom over the course of the exhibition. This show will have the finished 27 foot weaving that I made on the loom I built in the East Stroudsburg University Madelon Powers Gallery for my 2021 solo exhibition there. (See photo below.) Before I did the warp weighted loom, I used a pin loom to “sketch” in the same naturally dyed, reclaimed fibers I eventually used in the warp-weighted loom. These modules were the models for the large paintings I made-on repurposed, reclaimed fabric of course-that are also in the exhibition. Since the modules are small, they can “dance” around the exhibition space, there are two dozen of them, see if you can find them all! While dyeing the fabric, I was kind of gob-smacked to learn that some of the pigments that I had been painting with for decades were originally made using leftover dye baths! I took a deep dive into making my own pigments, and paint during my residency at the NCC East 40. I did a series of imaginary landscapes on clay panels I made, where ALL of the colors were paints I had made from pigments I processed. This show will include most of these imaginary landscapes. So for example you can see weavings that include fiber dyed with madder root, and paintings that use paint made from the leftovers of the dye bath used to dye that fiber in the same show. These natural landscapes also include paints made from clay dug from the NCC East 40, and ceramic works made utilizing that same clay. The ceramic works are the most recent, except of course for the weaving that will be performed over the course of the show. A through-line and progression here are the materials-from the earth-that are used in all the work.

When I began working in ceramics all those years ago (the 1970’s!) I can recall being disappointed, first in high school and then in college, at the “lack” of color in the available glazes. We all had our boxes of crayons bursting with color, and even the cheapest mass-produced consumer goods were glaring with color. Even today, consumer goods (even foods) are bursting with artificial color. We inhabit mostly a built environment (how often are you out in nature?) where a cacophony of accidental color prevails. For example, I’m thinking of a very tastefully designed lounge, with all the furnishings and carpets and such color coordinated-inhabited by people sporting all kinds of colors, carrying bags and things with even more crashing colors that were most decidedly not a part of the designer’s scheme. I think we learn to ignore all these clashing colors as some kind of self-defense mechanism. I have to admit, it could be age. But it could also be looking at lots of great pottery-Bernard Leach, Shoji Hamada, Michael Cardew, Phil Rogers, Matthew Blakey and plenty of works by unknown potters in museums-I’m coming to appreciate the palette of winter. It’s like a palette cleanser for the eyes. For me, the browns aren’t neutral. Some are russet, some cool, some tawny, and these browns are punctuated (some days) with blue sky, and evergreens wearing their dark green winter coats. And when it snows, the blue sky is replaced by white, silver and a range of greys as varied as the browns they cover, to varying extents depending on how much it snowed. Don’t get me wrong, I still love the deep saturated colors of medieval stained glass, for example, but I’m also appreciating the subtle symphony of colors that winter offers. Even as a child I loved drawing bare trees, fascinated by the spooky dark trunks and branches, the more gnarled the better. But the NCC East 40 is mostly meadow. The mountains, ocean and even forest that I always tended to associate with “nature” just are not there. Much like the winter palette of colors, which I’m enjoying more and more, I’ve come to appreciate the subtlety of the forms of the meadow. Today a new revised reprint of Bernard Leach’s classic tome “A Potter’s Book” arrived. This edition has color versions of most of the pottery examples, and they are very much in keeping with the winter landscape.

Right now I’m perfectly content to inhabit the colors of winter.  Interior of the wood kiln at the Stahl's Pottery. You can see where the flame, heat and smoke came up from the 4 fire boxes in the floor; the pottery was put into other plain pots called "saggers" which were stacked floor to ceiling before the kiln was fired. 16 vents in the roof provided a draft to the chimney. I had two main reasons for going to the bi-annual Stahl Potter festival on June 15. One, I found out James Chaney, who I studied with 1978-80, was going to be there and I just had to tell him in person how great his instruction had been, and how I was building on it all these years later. The other of course was to see the historic pottery, and in particular the wood burning kiln.

Not long after I met the man who has now been my husband for 25 years, he asked me what kind of architecture I liked best. It’s not a question anyone had asked me before, but my pause was under a minute; Victorian Gothic. What might practitioners of Victorian Gothic such as A. W. Pugin or John Pollard Seddon, for example, possibly have to do with a Pennsylvania Dutch Pottery-or Colonial Revival for that matter? Yes, I know this seems very fractured, but it was the trip to Stahl’s Pottery, and reading the book “Stahl’s Pottery of Powder Valley” that connected the dots. My mother despised all things Victorian and idolized all things colonial, so that adds a family historical twist to this aesthetic conflagration. Let me begin to unpack this aesthetic cacophony. The book has a chapter “Arts and Crafts and the Colonial Revival” and the “Arts and Crafts Movement” was invoked on multiple occasions as I toured the pottery and museum. When I think “Arts and Crafts” I think of 19th century and especially British artists; William Morris and Edward Burne-Jones for example, and if American, maybe Gustav Stickley, not of Colonial American revival. But there are commonalities, and my visit to the Stahl pottery got me thinking about them-and my own heritage. It’s easy to think of any revival, be it Victorian Gothic, Colonial or Arts and Crafts Movement, as an imitation; as something less-than the original. But William Morris, whose designs are still popular, did not simply copy older prototypes-he made new designs for a new age, an age that keenly felt the loss of the individual craftsman in mass-manufacture. (It’s a bit mind-breaking that mass manufacture is overwhelmingly how those of us in the twenty first century have ready access to his designs.) And that was the big epiphany-that these “Historiated” styles, when done right, are new inventions originating out of the needs and circumstances of their own times, not less-than imitations of something that is done and over. The Stahl brothers learned pottery from their Victorian father. In the early twentieth Century they shut down the pottery they inherited/tried to carry on from their father, because they couldn’t compete with mass-manufacture. But they opened their own pottery three decades later because the values of the Arts and Crafts movement begun in the nineteenth century had taken root here, in the twentieth century, and the literal value of the kind of work they had done for their father had multiplied. In the midst of the Great Depression no less, the Stahl bothers opened an old style pottery with wood kiln, what is now the Stahl’s Pottery Historical site https://www.stahlspottery.org. I didn’t see my mom’s fascination with the colonial as more than her personal taste; I didn’t see it as part of a larger historical phenomenon. My mother seldom could use the word “Victorian” without the accompanying adjective “monstrosity.” (I suppose my way of rebelling against my mom was a Victorian aesthetic.) I was missing the through lines, of Arts and Crafts, Colonial Revival and my own aesthetics. The Stahl brothers weren’t imitating the work of previous potters; they were doing their own work. The interesting thing with arts and crafts is that when you do things with your own hands, it’s actually hard not to put yourself into what you’re doing, even if you’re using traditional materials and techniques. And those who pick up those pots, or look at those paintings or wear that hand knitted sweater etc. see that human element, which only becomes more precious the more impersonal products become in our society. |

Cindy VojnovicArtist & Educator Archives

September 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed