|

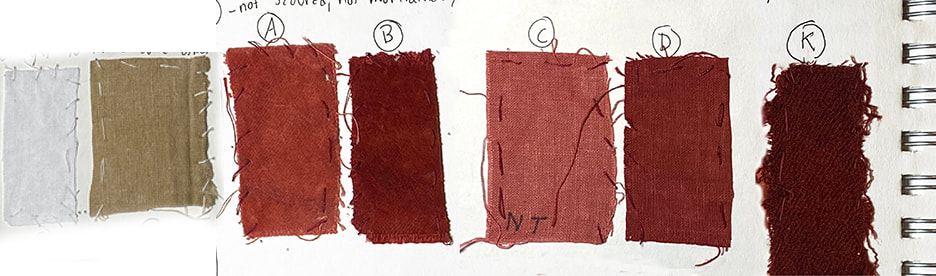

Doing a madder dye pot is something of a long term commitment! There is so much you can get out of it, if you do everything just right. Madder is a plant, the dye color comes from the root, and you can’t harvest the root until the plant is at least 3 years old. The root from the madder plant can make my favorite color in the world-a rich, warm dark red. Madder can also make orange, pink-or brown if the temperature gets too high. The leftovers from the dye bath can be precipitated into a solid pigment (see my 4/29/22 post “Don’t Jump in this Lake”) from which can be made pretty much any kind of paint-oil, watercolor, gouache, pastel, egg tempera etc. The ancient Egyptians used it, the Greeks and Romans used it, it was very popular in the middle ages, Renaissance…and some version of “Madder Lake” or “Rose Madder” has been in my paint box from when I started painting many moons ago until now. All of the above-from antiquity to me-used madder both to dye fiber/fabric and to make paint. You need a lot of madder to get the strong red that’s my favorite color. I’ve had a beige (what was I thinking-me-beige???) sweater, ramie and cotton, for literally decades. One of the reasons I never wear it out is that I don’t wear it much. It fits great. It’s comfortable. But…I’m just not a beige sort of person. I decided that in this dye pot, I would solve two problems; the beige sweater, and getting a rich red on cellulose, which would be for example cotton, linen, hemp bamboo etc., that is vegetable and not an animal fiber like wool. Wool soaks up madder like a sponge, think of the wool Persian carpet reds, they historically used madder for those. But I have repeatedly failed to get a decent red on cotton. I have to admit, if I ever wanted something in pink, the pink from madder is really lovely. But I don’t want pink, I want that deep intense red. So, this time, I pre-treated my sweater and other cellulose fibers with oak galls; anything with a high tannin content would do, but oak galls are as good as it gets with a natural tannin. Black tea has tannin, pomegranate skins have tannin, so does the oak leaves, bark and other parts, but the galls-the tree’s defense agains a wasp-have more concentrated tannin that doesn’t discolor as much, or at least that’s what I’ve read. In fact, when I pre-treated with the oak galls it turned the fabric tan. BUT-I finally got good reds from cellulose! Look at the swatches! I tried several fabrics both with and without the tannin pre-treatment, and the results speak for themselves. And the sweater is now a lovely color-I can’t wait until it’s less than 90 degrees and 100 percent humidity to wear it.  If you look at the swatches A & B also C & D are the same fabric, dyed in the same dye bah for the same time. The difference was B & D got pre-treated with tannin from oak galls. Far let, same fabric as C & D, showing the natural cotton hemp fabric far left, and treated with tannin next to it. K is wool that was in the bath less time than A-D, showing the super deep red.  After a chemical reaction to precipitate the dye into a pigment, the hard work is getting rid of the water to make a dried pigment. In the smaller clear container upper left, you can see how the pigment is collecting in the filter, and the clear liquid accumulating below. Same thing is happening in the big bucket, I'm using fabric in a kind of colander as my filter. Far right, you can see the pigment spread out to dry on a pane of glass. See 4/29/22 post for more on this process It’s not unusual to keep a madder dye pot going for a week or more. You bring the temperature up to 150-160 degrees F. for 10 minutes to an hour, then let the fabric sit in the warm pot, day after day, until it gets to the depth of color you want. At a certain point, the fabrics just don’t get darker. At that point, there are choices. You can get lighter colors, you can add something acidic to get orange-or you can make the leftovers into a pigment. I didn’t have things I wanted to dye rose or orange, so I made a lake pigment. I’m very curious to see how the color will compare to the lake pigment I made this past winter.

But wait, this is madder, so that’s not it. I strained the roots out of the dye pot before I made the lake pigment. Today, 11 days after I first began working with those roots, I put them in fresh water and started a new dye pot. Like I said, madder is a long-term commitment. Too long for one blog post, I’ll have to post again to let you know what happened with round two of madder dye pot #8. I keep a “dye-ary” of all my dye pots, and so I know that yes, this is the 8th madder dye pot I’ve done so far.

0 Comments

I like considering everything in a painting, every material that goes into it, and this summer's residency gave me an idea. I did extensive work in clay in my first half of undergraduate, and even though that is now ancient history, I still remember enough to take advantage of the ceramic facilities at the NCC East 40. I have to give credit to Joni One-Benintende, a phenomenal ceramic artist, for inspiring me to paint on clay. She does it in a way you see it as a sculpture, and assume the color is the clay or a real glaze, not “just” painted. What I’m doing, coming at this from the perspective of a painter is going to be very different. I had to mention Joni however, because seeing a solo exhibition of her work at East Stroudsburg University’s Gallery about a year ago is what sparked my interest in using clay as a painting ground. I just love the pun-get it-clay as a ground, ha ha! When I used old clothing as a painting support, I didn’t want the fact that it was old clothing to become invisible. I wanted you to see it was old clothing-but only if you looked close enough. Likewise, I don’t want the clay to be some sort of imaginary blank slate. I like to partner with the materials I’m using, not force them to be something else. I want the clay to look like clay, even after it’s painted, I don’t want the clay-ness to be incidental. On the other hand, at least for now, I’m not making sculpture; I do want a “picture plane” of sorts. I could roll out the clay with a rolling pin and trim it to a precise shape, but I’m not. I’m throwing the clay around so it stretches, cracks, and to a certain extent defines its own edge. On the back of the slab I build in some sort of hanging “hardware” that also serves to put the picture plane in front of, not flush with the wall. Or, the table or whatever it’s on-I haven’t ruled out putting the paintings other places than a wall. From what I’ve found, there are plenty of people using acrylic on clay, but for oil, I have to just wing it, I could not find any advice anywhere. I’m not saying no one has done this, I am certain someone must have/be doing it. Knowing what I know about painting technology, I decided that after firing, I would size the clay with rabbit skin glue. Some sort of hide glue, especially rabbit skin glue, is what everybody used historically on any kind of canvass or wooden board before acrylic gesso was invented. I’ve used it on fabric, it’s a great surface to paint on and it’s clear so the clay is still entirely visible. I have some sculptures in my garden that I made around 1979 or 1980, that were only bisque fired. They are getting green from whatever organic thing is clinging onto them, which is really cool since I want them to naturalize into the garden, and never intended to paint them. If these old bisque-fired sculptures can last outside year in year out, I’m figuring bisque is good enough for paintings intended to stay inside, but I do have some that are high-fired. I began “doodling” in egg tempera on the back of one of the fired & rabbit skin glue sized slabs; it takes the paint great. In this shot, you can see the “hanging hardware” in the form of clay strips with built in hoes for wire or string. Sorry I don’t have any finished paintings, so far I’ve been generating the materials to make the paintings, but when I have my first finished painting, I’ll be sure to post it here!

I’m a sucker for historical practices and I’m growing woad, so I just had to make woad balls. If you look at my June 28 post, “The Mother Woad” you’ll see my, how my woad babies have grown, and can learn a bit more about woad, but essentially It’s a plant source of blue dye and pigment. So what’s a woad ball? Well yes, it’s a ball of woad, but it’s more than that. It’s actually a first step in fermentation and processing of the plan. Historically “Woad balls were very valuable and used for trading.” http://www.thewoadcentre.co.uk/the-history-of-woad/ For me, on a pragmatic level, woad balls allow collection at the optimum time for harvest, concentrates the active ingredients of the plant matter and preserves it for future use whenever I want to actually use it. It’s not easy to find anyone selling woad balls or pigment, I don’t know of anyone in this country who sells the processed version, as opposed to the seeds. It was essentially replaced by indigo grown in hotter climates than where I live. Let me digress here to explain the term “indigo.” To quote Wikipedia, “Several species, especially Indigofera tinctoria and Indigofera suffruticosa, are used to produce the dye indigo.” So the word “indigo” can mean the dye or pigment, or it can mean some of the plants that can make it. Woad produces indigo, but not at the high concentrations of, say, Indigofera tinctoria. So why bother with woad? Part of it is climate-I can grow it locally, and part is curiosity since it was used so successfully for so many centuries by my ancestors. In the few dye pots I’ve done so far with woad, it is not identical to indigofera tinctoria etc. that are generally used for what is generally called indigo. Let me give you a food analogy; popping vitamin C pills will give you way more vitamin C than broccoli or an orange; but that doesn’t mean that the broccoli or the orange should not be eaten and you just eat capsules of whatever nutrient. By just taking a synthesized version, you’re losing out on a lot of other stuff. I’m curious to explore this plant (woad) that was the main source of blue for thousands of years. The photos above are screen shots from video I took. I need to edit the videos into something that makes sense, keep checking back to the blog, I'll let you know where to find them.  The finished woad balls. You can see the woad plants in the garden plot above the board with the woad balls on it. I didn't harvest all the leaves, there will be more to come, the first planting is growing fast. On the right side of the bed, it's hard to see but there is a second planting that is coming along. This week Sierra Heath walked into the breezeway where I was working with a bunch of yarrow she had just harvested from her garden plot not that many feet away. It was irresistible, I have never died with yarrow before, so got started right away. Yarrow, like most natural dyestuffs, should be equal in weight to the fiber being dyed. Since it wasn’t a large quantity, I decided I wanted to do swatches of 7 different fabrics plus embroidery floss as a kind of test, along with some nice bias silk ribbon that is pretty light to get the most “bang for my buck” on the 50 grams of yarrow I was given. Yes, I weigh in grams, the math is so much easier than working with ounces. I prepared the pot by putting the yarrow in the pot with water and heated at 180-200 degrees F for about an hour before straining out the plant matter. I put the fibers in and after only a half hour, the wool was a gorgeous, buttery yellow but the rest of the fibers were only weakly colored. I took out the wool so it wouldn’t hog all the dye, it was already perfect and didn’t need anything more. I left everything else in the pot for the full hour that is usual for yarrow. By that time the silk/hemp charmeuse blend was a gorgeous color, but the rest was frankly a bit anemic. One thing I’ve learned from natural dyes, just keep going if you’re not happy with something as-is, there’s always something more that can be done. I thought of copper because the yellow of the too-light fiber was cool, tending towards green anyway. I keep a jar of copper things-cut off bits from pipes, wire and scrap metal from past jewelry projects, soaking in a vinegar/water solution on my kitchen counter. (Doesn’t everyone have one sitting on their kitchen counter?) I brought the jar to the East 40 the next day and dipped the too-light fibers in the copper. Almost immediately, without even warming them up, the copper deepened the colors! You can see for yourself below-the bias cut silk on both the left and right were from the same roll of ribbon and dyed in the same yarrow pot. The only difference is that the pile on the right was dipped in my homemade copper bath! After taking the before-and-after copper bath photo, I took the plunge, or should I say the fiber took the plunge into the copper bath. Not only did I like the color of the copper-dipped fiber better, copper actually increases color-fastness. Next up was to over-dye with indigo (blue), inspired by the cool/greenish hue of the yarrow on the silk and cotton. My hunch was correct-I got some lovely greens.

I tried to make a lake pigment from the leftover dye, but failed. I’m not sure if it was PH issues or if yarrow doesn’t work for making lake pigments-probably my error. My water at home is PH neutral, so I keep forgetting to amend the acidic water at the East 40 before starting a process like making a lake pigment where that is critical. In the past, I could not get a good light blue with indigo. I finally sprung for 3 of the Michel Garcia DVD sets, they have 2 disks in each set, and got some great information about how to get a light blue. Indigo is not soluble in water, it’s a pigment, and historically there have been endless variations from nasty smelly two week or more old urine, to contemporary nasty chemicals that have been used for what we can a “vat” to reduce indigo into a soluble form. I used the Michel Garcia 1-2-3 vat, which uses indigo, fructose and pickling lime. Not nasty. In fact, both the pickling lime and fructose I bought are marketed and sold with the intent of being used in food. The basic idea (ph pun, sorry) is to make the dye bath alkaline and “reduce” (take the oxygen out of) the indigo so it becomes temporarily soluble in water, long enough to get it into the cloth fibers. When you take the cloth out of the vat it should be green! On exposure to the oxygen in the air the indigo once again becomes insoluble, but at that point trapped in the fibers. I made the starter solution for the indigo vat in a quart mason jar. I actually have a nice blue bucket that I have dedicated to using as an indigo vat, but one advantage of making a starter solution in a glass jar is you can see what’s going on better. Below, you can see how on the left the pigment isn’t because it’s too blue, especially at the bottom and top. But on the right, the bottom is a dark green and above it is a kind of brown; only at the top, which is exposed to oxygen, is it blue. This is actually what we want-on the right, the indigo is reduced. From the top view of the jar, you see the bubbles and the metallic sheen; YES. This is what we want to see. I heated water up to 120 degrees and put it in the 5 gallon plastic bucket, then added the starter solution I had made in the quart jar. Back to the light blues; if you don’t get the indigo deep enough into the fibers, you end up with the color only on the outside of the fabric where it can rub or wash off. The solution (oops, another pun, sorry) is a very weak dye bath, so that you can soak the cloth in the bath long enough to get the indigo deep into the fiber. (Duh, why didn’t I think of that. I suppose that’s why I paid to get the DVD’s, Michel Garcia gets the big bucks.) I used only 1 tablespoon of indigo in my dye solution, for two and a half gallons of water in the bucket. For the residency, I was able to get 4 new fabrics that I had not worked with before, and was eager to test how each would absorb the dye, so I cut strips of each of the 4 fabrics. After soaking the fabrics in water, each got 3 dips for about a minute each in the dilute indigo vat. Above, you can see these strips on the drying rack. From left to right, pure wool gauze twill; this was unbleached, and had a yellowish look before dyeing. I was actually quite happy with the greenish tinge on this. Then, hemp silk charmeuse, hemp cotton muslin and finally on the right bamboo rayon.

On the drying rack photo above, I had not yet rinsed the fabrics. I wondered if the kind of mottled appearance was because I hadn’t ironed the fabrics before dyeing, but then when I rinsed and ironed them the blotchiness went away. What I just learned is that because water has so much oxygen, I could have rinsed them before letting them dry. What’s nice about natural dyeing is that there can be such nice results all along the way. A beginner can do something stunning, but there’s always more to learn. Last winter, after I made my first lake pigment (4/29/22) the first paint I made with it was watercolor. I have a small watercolor book, so I just smeared on to see how the paint worked. It suggested a landscape. I added other colors on as I made more pigments, and then paint from them. There was something that really interested me about doing an imaginary landscape. I tend to be terrible at drawing or painting from imagination, so for me this is going out on a limb. But there is something really intriguing to me about how many landscapes I’ve viewed in my lifetime have imprinted on me. The East 40 is a very different landscape-than where I live, and what I’m drawn to. I tend to be drawn to mountains, forest, and or rivers or oceans, but the East 40 has no pond, no stream, and is completely flat, with only a couple shallow tree lines. I’m not sure how this is going to play out in the actual paintings. It may not work out at all, and I might have to change course. Or ? Not to sound like an old TV show, but stay tuned for future episodes-I mean blog posts-to find out.

I like considering everything in a painting, every material that goes into it, and this summer's residency gave me an idea. I did extensive work in clay in my first half of undergraduate, and even though that is now ancient history, I still remember enough to take advantage of the ceramic facilities at the NCC East 40. I have to give credit to Joni One-Benintende, a phenomenal ceramic artist, for inspiring me to paint on clay. She does it in a way you see it as a sculpture, and assume the color is the clay or a real glaze, not “just” painted. What I’m doing, coming at this from the perspective of a painter, is going to be very different, but really, I had to mention Joni because seeing a solo exhibition of her work at East Stroudsburg University’s Gallery about a year ago is what sparked my interest in using clay as a painting ground. I just love the pun-get it-clay as a ground, ha ha! When I used old clothing as a painting support, I didn’t want the fact that it was old clothing to become invisible. I wanted you to see it was old clothing-but only if you looked close enough. Likewise, I don’t want the clay to be some sort of imaginary blank slate. I like to partner with the materials I’m using, not make force them to be something else. I want the clay to look like clay, even after it’s painted, I don’t want the clay-ness to be incidental. On the other hand, at least for now, I’m not making sculpture; I do want a “picture plane” of sorts. I could roll out the clay with a rolling pin and trim it to a precise shape, but I’m not. I’m throwing the clay around so it stretches, cracks, and to a certain extent defines its own edge. On the back of the slab I build in some sort of hanging “hardware” that also serves to put the picture plane in front of, not flush with the wall. Or, the table or whatever it’s on-I haven’t ruled out putting the paintings other places than a wall. From what I’ve found, there are plenty of people using acrylic on clay, but for oil, I have to just wing it, I could not find any advice anywhere. I’m not saying no one has done this, I am certain someone must have/be doing it, just didn’t find them. Knowing what I know about painting technology, I decided that after firing, I would size the clay with rabbit skin glue. Some sort of hide glue, especially rabbit skin glue, is what everybody used historically on any kind of canvass or wooden board before acrylic gesso was invented. I’ve used it on fabric, it’s a great surface to paint on and it’s clear so the clay is still entirely visible. I have some sculptures in my garden that I made around 1979 or 1980, that were only bisque fired. If these only bisque-fired sculptures can last outside year in year out, I’m figuring bisque is good enough for paintings intended to stay inside, but I do have some that are high-fired. I began “doodling” in egg tempera on the back of one of the fired & rabbit skin glue sized slabs; it takes the paint great. In this shot, you can see the “hanging hardware” in the form of clay strips with built in hoes for wire or string. Sorry I don’t have any finished paintings, so far I’ve been generating the materials to make the paintings, but when I have my first finished painting, I’ll be sure to post it here!

Earlier this summer I got to see the Pompeii in Color exhibit. As we all know, Pompeii got buried in volcanic ash, which must have varied in temperature-because there was a painting that showed the effects of heat on only parts of what started out as a monochrome yellow painting! (See photo above.) Tens of thousands of years before Pompeii, humans discovered-and used-the trick of changing the color of earth pigments with fire. I’m a kind of artistic re-enactor, so I wanted to take the fabulous “garden gold” that was dug from the Earth on the NCC East 40 where I’m doing my artist residency this summer, and “burn” it. From the very start of me painting, which is-ahem-a lot of years ago, I have been using burnt sienna and burnt umber, in addition to their unburnt versions, raw sienna and raw umber. Anyone who paints will be familiar with these basic earth colors, and yet, apparently there aren’t lots of weirdos like me who want to burn it themself. I got the idea of putting the dry, powdered garden gold pigment (essentially clay with the impurities taken out by Walter Heath and NCC ceramics students) into a in tin “kiln” just like I did with the vine, see yesterday’s (7-1-22) post. I actually did the “burn” in the same fire as the charcoal and vine pigment, but decided one long post on both would be too long and complicated. Below is my porcelain palette with the garden gold pigment before firing (left) and after (right.) I had a fairly tall tin, and only filled it about 1/10 full. I have zero idea if that made any difference. Well, maybe I can hazard an educated guess. I do know that metal conducts heat, so maybe if the tin were full, the pigment in the center would not have reached as high a temperature? Honestly, I don’t know. I also had no idea how long I was supposed to fire the pigment to get the red color. I just did it an hour like the charcoal. TA DA-IT WORKED! I’m super happy with the color of the burnt pigment, and want to do another burn because I didn’t do enough. That second burn could vary, lighter or darker. Much like my approach to natural dyeing, I get delighted by all the variations I can achieve, I love making colors. I’m not a factory. I suppose you could say it’s a kind of boutique approach to making color, and I have no desire to become a factory. My idea for next time would be to put some rocks in with the pigment. Rocks, I know, also conduct heat, so if I pack the tin so the rocks are as close to the center as possible, all the pigment should get heated up. That’s my theory anyway. Egg tempera is my go-to making paint to do tests. You don't have to make a whole tube, I used the pigment in the photo above, added some egg yolk, mixed with a martini stirrer right in the palette and presto, it was ready to make the paint swatches below. I have to admit, I haven't cracked any of the rocks I burned in the fire on Wednesday. The color of a solid rock is not always the color of the pigment it makes, so I have one more surprise waiting for me when I get a chance to grind those rocks and see what colors they make.

“Vine” and “willow” are the two most popular types of charcoal sticks for artists. Often my students are surprised to learn what a primitive material this is, and that “vine” refers to the stems of grape vine and “willow” branches of that tree. It’s likely that charcoal was the first drawing material, simply taken from wood that had cooled off after a fire. Certainly, charcoal was used tens of thousands of years ago, as cave paintings attest. Chunks of charcoal off a log are not elegant drawing tools. The charcoal sticks Drawing I students get to know up close and personal would not be possible with just grabbing stuff out of a quenched fire. Mother Earth News, The book The Organic Artist and many other sources all recommended the use of a lidded tin with a small hole punched in the top for steam to escape. You don’t want ash, you want the black charcoal and not any of the grey ash, and with these tin “kilns” that’s what I was hoping to get. I used empty cookie, tea and other used tines, even a little mint tin. I chose to make vine charcoal, because I have a grape vine in my back yard. I’ve been told February is ideal grape vine pruning time, so last February I did a major pruning of my vine, and packed the contents into the tins. The idea is to pack them in tight so they don’t warp when fired, but retain a straight stick form. It involves a lot of cutting and you’re also supposed to strip the bark. I didn’t put the lids on at first, to give them a chance to dry out. Then I put the lids on and didn’t open them up until I wanted to show someone how they were packed before I put them in the fire. There was some kind of mold that had formed in-between the sticks. Gross. But it wasn’t like the sticks weren’t bone dry; they weren’t rotted, I was hoping the mold would burn off in the firing. On June 29, I made a fire in the fire pit out at the NCC East 40. I had read conflicting information about the actual fire; one place said you have to have hardwood, and don’t put the tins down until there is no flame; like how my dad would cook food on a charcoal grill the the backyard. I always was surprised that he waited until there was no flame, and said the coals were hotter than the flame. Another sources said build the fire around the tins, and showed a photo with flames engulfing the tin “kilns.” There was cardboard and scraps of wood from who knows what that were already in the fire pit, so I assumed they were good to burn. I looped the cardboard so there would be air in the middle, put the tins on top of the cardboard and packed the wood around the tines so they wouldn’t fall off the cardboard. It worked! The next thing is to wait around an hour after the fire gets hot. I’ll bet the cave people didn’t time this with their phone, but I set the timer on mine and watched the fire closely. The other thing is, if you see fire shooting out the hole-or if steam stops coming out of the hole-you have to quench the fire a.s.a.p. I had a big bucket of dirt and a shovel. Someone had left a charred wok near the fire pit, I decided that would be where I put the tins before dumping dirt on them. Not surprisingly, the smallest tin was the first to flame. I quenched it and keep watch on the rest. I forgot to put a hole in the largest tin, which I found out the hard way-the steam forced the lid open. I put a big rock on the lid. Eventually, fire started shooting out the side of the lid, and so I had to quench that. The smaller pieces were fine, even in the big one that didn’t have a hole. I think the steam just got out the side of the lid, but the lid didn’t blow off because of the rock. When the timer went off on my phone, I took the rest of the tins out of the fire (scooped them up in a metal shovel) and dumped dirt on them. I waited about a half hour before testing if I could take the dirt off the hole in the top of the tins, starting with the little one, using heat-proof gloves and tongs. I moved all the tins to the breezeway, where I put them on fireproof concrete board. Sandra Zajacek and Michael did some clay experiments after I was finished with the fire, so I got out of quenching the fire at the end. The next day, I opened up the tins and discovered that my success rate was really close to 100%. No ash. Just a couple of the largest pieces from the big tin that need some more fire. You can always fire again, but if you get white ash you have lost your material and have to start over. So all in all, I was thrilled. This post is so long, I’ll make the next post about the color change in the pigment I fired. One last photo, me testing them out on a page in my notebook. I found I had some really great sticks, and a variety of hard to soft, thick to thin. They marked and smeared easily, but weren’t too soft, so you could smear and still see the lines if I wanted. Honestly, I’m astounded it worked so well.

|

Cindy VojnovicArtist & Educator Archives

September 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed