|

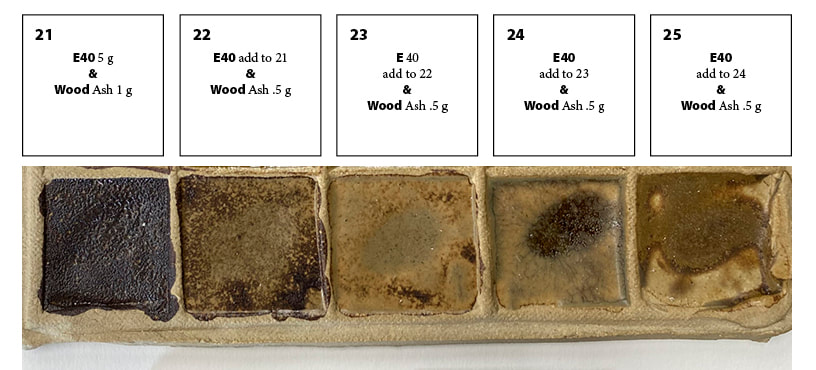

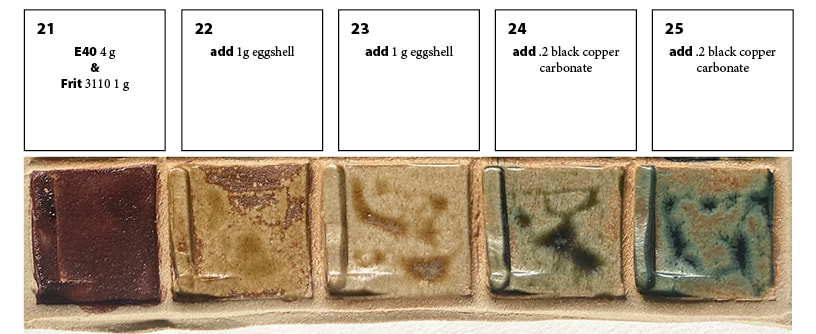

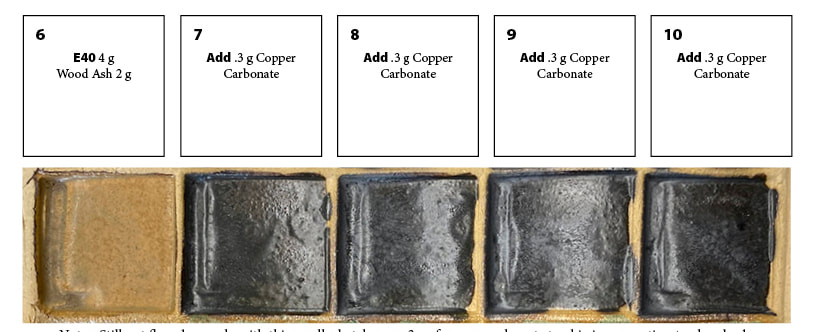

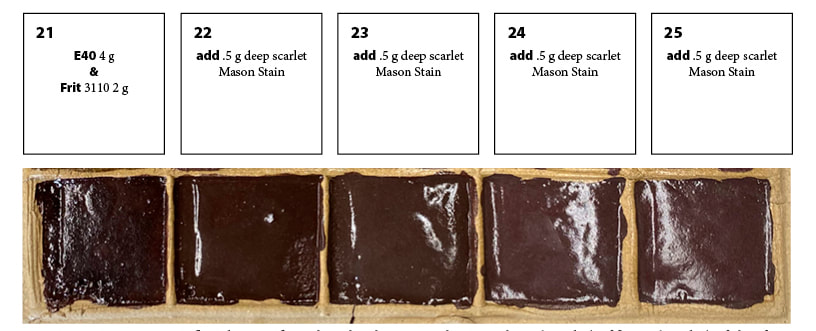

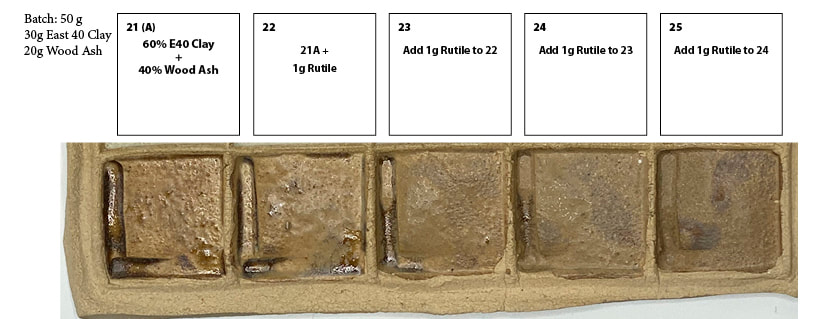

This summer I am working to formulate glazes and a clay body from the local clay dug from the Northampton Community College (NCC) East 40. https://www.ncceast40.org I’m weird; for me, waiting for the next glaze test to come out of the kiln is like a kid trying to wait to unwrap a present. But while I’m waiting for the tests that will come out of the kiln on Thursday, I thought I’d make a post about the preliminary testing I’ve already done. Spoiler alert-I’m going to show you the best first, see above. To set this up, you have to realize that the clay at the East 40 is very rich with ingredients (probably iron, maybe manganese) that go very dark when fired to the high temperatures (roughly 2,380 degrees) we use for our glaze firings. I discovered a “magic powder” from my kitchen, that makes the East 40 clay fire light, and opens up striking color possibilities! I get eggs from a local farm, and if you’re familiar with truly free-range eggshells, you realize they are at least twice maybe three times as thick as factory farm eggshells. That's why eggshells build up fast at my house! Eggshells are on average 95% calcium carbonate, and calcium carbonate is one of the most common and useful ceramic ingredients. In glazes, calcium carbonate is usually sourced from whiting or talc. Eggshells, when fired, shrink in volume tremendously, which can cause problems in glazes. I did a preliminary bisque firing of my ground up eggshells, so that the shrinkage would happen BEFORE I put them in a glaze. You can see on the left in the line blend above, how dark the East 40 clay fires even though tis test was fired at a lower temperature than we use in the gas and wood kiln firings at the East 40. But wait! Add a little eggshell, (second from left square) and the color changes. Add a little more (center) and wow, a totally different glaze color, without adding any colorant!! But wait, there’s more. Add a little black copper oxide (colorant) and you get one green, a tiny bit more and you get a different green! I designed an entire 25 section biaxial tile-5 rows of squares by 5 rows of squares-investigating the interaction between 4 ingredients, as inspired by this line blend. All of the variations use the East 40 clay, and wood ash which is used as a flux (an ingredient to melt the clay into a shiny glaze). The balance of East 40 clay to wood ash is varied, explored both with and without the other two ingredients, the eggshells and the black copper oxide. Look for a post on when this tile comes out of the kiln!  Like the tile above, this was the last row of a 25 section tile. Note that on the left, there is not enough wood ash to melt the clay enough to make a smooth and shiny glaze. Moving to the right, I'm adding a little more wood ash in each square. by tile 25 it loses the rocky texture of the first tile, getting closer to a usable glaze. Adding Wood Ash to East 40 Clay This test uses only two ingredients. Going left to right, I added increments of more wood ash to the East 40 clay. A few notes about this; for the ceramic artists out there, this was cone 6 oxidation. It's obvious that the 5 parts clay to one part ash is not nearly enough ash. (The ash is used as a flux, that is, to help melt the clay into a glaze.) I made impressions into each square with a finger, making a kind of "lake" within each square, and also applied the glaze unevenly to see how various thicknesses of the glaze would work. I'm working with such tiny amounts here that of course more testing is needed to nail down percentages, but it's pretty clear that the wood ash I was using, which was from the wood kiln at the East 40, needs to be over half the mix to melt the clay. I'm currently working on glazes for cone 10, so at that hotter temperature obviously everything will melt more than at this cone 6 (lower temperature) test. Adding a colorant I wish I had done the line blend of just the clay and wood ash first! Here there isn't enough wood ash in the mix to start, and as you add a colorant like copper carbonate, that tends to retard melting and make matters worse. Note that even .3 grams is way too much colorant for a first step! Instead of green, which we would expect from copper carbonate, we're almost at black. That's why I start with simple line blends-I'm not using much in materials to get this kind of information that points me in the directions I should go. Above, I used 4 g of East 40 clay to 2 parts of a commercially produced flux, the same percentage of clay to wood ash from the last test. The commercial flux has a stronger action but even so, it's under-melted. I'm using a commercial mason stain for the colorant. The main problem is that the clay when properly melted into a glaze is so inherently dark, it's hard to notice much color difference from the base glaze at left with no colorant. In the basic mix at left before I started adding rutile, it's melting ok but not great. Rutile can add color, texture and odd what I'll just call variations to the look of a glaze. Like the cobalt carbonate, it also makes the glaze more matte, or under-melted, under vitrified in ceramic terminology. Matte glazes are a thing, we don't always want super glossy glazes, but they can be more prone to leaching and other defects/weaknesses. I do want to do more tests with rutile going forward, just that every time I add an increment of rutile I know I need to add an increment of flux (melter) at the same time.

The way-back story I first used this clay when I was working on my master’s thesis, using a simple mix of half East 40 clay and half of a commercially available clay to make loom weights. (See crossing in my portfolio section) In my summer of 2022 Residency at the East 40, I used the clay, raw and roasted in a bonfire, as pigments for paints that I made and used in the “Imaginary Landscape” series of paintings that were featured in my Fall 2022 solo exhibition. During the residency, Walter Heath saw me grinding up rocks for pigments, and immediately had visions of using them to develop glazes. That summer I wasn’t ready to go there-but in 2023 I began preliminary testing, not just for the East 40 clay, but from local rocks I had picked up and processed. In this post I’m only showing the initial line blends I did with the East 40 clay, omitting all the rock glaze tests and tests on clay I dug out of my front yard-it’s a long enough post as is!

2 Comments

There is something about the weirdness, and richness of Medieval Art that has been an inspiration to me ever since I can remember. But just in this past year, I came across a Medieval wine pitcher (see photo above) that pitched me into a new series of work in ceramics.

I love that this guy’s hands are circles with lines through them, and his arms a simple single string of clay. I love that we still see them as hands and arms; I could give many more examples on this and other pieces but the point is, it’s this leap of imagination that intrigues me. Bestiaries are another related concept in medieval art that inspires me, how species could be mixed and matched, and become a new creature such as a griffin. And finally, I have always loved the flat out decoration of Medieval and Gothic things, from buildings to furniture to textiles etc. What fascinates me about the Medieval decoration is how a very few simple geometic forms can become incredibly rich and varied with repetition. These three medieval inspirations-weird abstraction, mixing of species and repetitive ornament-became the basis for a whole series of work in ceramics. I was so busy telling the story of firing the old wood kiln in part 1, I didn't include all the photos I had picked to go along with it! For more information of what these are about, ready part 1 from December 2, 2022.  In part 1 this was still wet on the wheel. Here it is fully fired. None of the other pots had protrusions like this one. I think that's because I had put woad inside, and we capped it with aluminum foil so that the woad vapors would stay inside. Something about that made whatever impurities were in the clay kind of pop out. This was the A body garden gold you saw me mixing in part 1 of this post.  This is the outside view of the cup above. I used 100% garden gold clay (dug from the East 40) using a brush I made from grasses at the East 40 to make the bush marks on the side. This was a commercial 119 clay body. I had made this for a demo before making the A and B body clays from the East 40 "garden gold." The primitive and labor-intensive processes of growing dye plants, making natural dye, making pigments including from the natural dye, making paints from the pigments and making clay structures to paint them on took up the bulk of this summer’s residency. Now I’m finally using all those materials! Around August first, I started using only oil paint I had made in the residency on the clay slabs, and then tried out the watercolor to tint a pencil drawing I had made of something (I’m not sure what kind of plant it is) growing in the community garden. After only 3 days of painting, it was pretty clear what was missing; a true brighter, lighter yellow and a more opaque white. Throughout history, from cave painting onwards, many artists have done amazing work with very restricted palettes such as brown, black and white. The most restrained color palettes, especially monochrome, nearly always use white. Problem is, modern artist paints generally use metals for white. Historically and to this day lead white was used, now mostly titanium and some zinc are used for white. The processes to make the metal paints are just not something I’m NOT going to get into, because of how involved they are, the equipment needed and how potentially toxic it can be. I first tried chalk from champagne, France-a natural white material I had on hand because it was used in the pastel and gouache paints I made. I quickly learned why chalk is used to make pastel and gouache-it’s almost transparent. If you add chalk to a paint or pastel, it changes the texture and working properties, but what you see is not so much the chalk but whatever the pigment’s color-blue, red, yellow etc. The chalk just wasn’t opaque enough. Making my own set of paints, and using them, has given me an appreciation of what is essential and what isn’t. I'm using far fewer colors, and it's frankly pretty interesting how far these few homemade paints can go. I plan to solve the white dilemma with white clay for white. I know white clay used to be mined from this area, and hopefully I’ll eventually be able to find some local white clay. With the residency over and fall classes almost here, I’m going to cry uncle and “cheat” with some commercially made white until I can make a white from clay. When it comes to the true yellow, I’m confident I can do this myself with natural, local materials. I have some dried weld that Marla grew for me in her dye garden, and weld is one of those dye plants that was historically used to make lake pigments. I’ve made lake pigments before, and I’m hoping to just make do with the garden gold until I can make pigment from the weld. At this point I haven’t cheated and used any commercially made yellow paint. I’m really enjoying exploring the imaginary landscape idea with my homemade natural paints on the clay slabs. I work on a bunch at a time, working on each a little each day, building up the colors. I do of course mix the colors, but I also use layers of translucent paint, where one layer is dry before I add the next layer. The layers are thin so I don’t lose the texture and properties of the clay slabs. The weight of the clay, the physicality is important. They are not images on a “blank” white picture plane. I’m not trying to illustrate a landscape, but to allude to one.

It’s hard to know when these paintings are “done.” I put two in the ESU faculty show that are so minimal that it was hard for me to accept they were finished. The show opens the first day of the semester, August 29, at the Dunning Gallery on NCC’s Monroe campus. There are paintings in progress in my studio that already have much more paint on them than the two in the show, but they are not “done” yet because to me they just aren’t doing everything they need to do as a painting. When a painting gets to a point where it doesn’t need anything-where if you did anything more it would make it worse-it’s done. The art is figuring out when you are at that point! |

Cindy VojnovicArtist & Educator Archives

September 2025

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed